The education of nearly 49 million children in Afghanistan, Sudan, Somalia and Mali is at extreme risk of collapse, according to new analysis by Save the Children on how COVID-19 combined with conflict, climate change, displacement, and lack of digital connectivity to derail children’s learning.

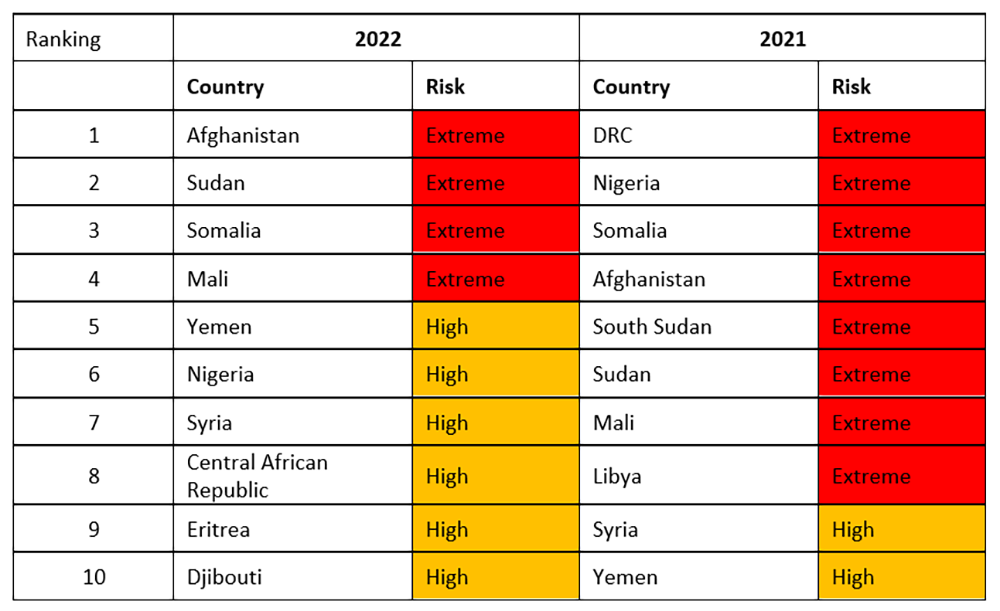

For the second consecutive year, Save the Children ranked 182 countries by the vulnerability of their school system to hazards that threaten children’s right to learn and by deficiencies in preparedness to confront these hazards. While the number of countries at ‘extreme risk’ has reduced since 2021 from eight to four - likely due to increased access to COVID-19 vaccines - the global hunger crisis that is now unfolding as a result of new and protracted conflicts, increased food prices, and extreme weather, is having additional impact on these countries’ education systems.

The analysis used the same methodology as the Build Forward Better report the agency released in 2021 and showed while some countries had made significant improvements, many stayed at high risk or had become more at risk.

Of the countries assessed, Afghanistan was found to have the highest level of risk, up from fourth place in 2021, meaning its education system has worsened since the Taliban gained control of the country over a year ago, jeopardizing children’s futures, particularly girls.

Afghanistan was closely followed by Sudan, Somalia and Mali, all of which also have education systems ranked as being at ‘extreme’ risk of ongoing and future crises disrupting education. Somalia was unchanged at third in the list while the risks to education in Sudan and Mali increased in the past year.

One of the biggest improvements over the past year was in Colombia where education was now classified at ‘moderate risk’ compared to ‘high risk’. The country moved to rank 58 from 28, partly due to better access to COVID-19 vaccines.

At the other end of the spectrum, Lebanon saw one of the greatest negative changes, rising to rank 32nd in the list from 68, partly due to the worsening economic crisis unfolding in the country where youth unemployment has increased sharply.

Of the 10 most at risk countries[i] with available Acute Food Insecurity Data, all show large populations with high levels of food insecurity. Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan, Yemen and Central African Republic all have more than 20% of their populations at Phase 3 or above, meaning they are all in the grips of a hunger crisis.[ii]

The climate crisis is further threatening children’s right to learn, as extreme weather events damage or destroy schools, and an increasing number of children will likely have to flee their homes, leaving behind their education.

Children out of school tend to find it harder to catch up on lost learning, and grow more vulnerable to hunger, violence, abuse, child labour and child marriage, especially girls, and children who live in low-income countries, in refugee camps and warzones.

Countries with high vulnerability and exposure to hazards such as climate change or health crises does not always mean the education system is at high risk of collapse. A country can have high-risk exposure, but good preparation can reduce the overall net risk.

Save the Children is calling for every country to have a preparedness plan to secure children’s learning and wellbeing in future crises.

The aid organisation is also calling on those governments with school systems with extreme or high levels of risks to take rapid action to avoid a prolonged learning catastrophe. These actions include increasing catch-up learning opportunities, prioritising teaching the basics, and ensuring assessments are in place so children can be placed in the class best suited to their learning level rather than their age.

Hollie Warren, Head of Education at Save the Children, said:

“The COVID-19 pandemic was one of the most disruptive and damaging catastrophes to hit children’s education in living memory. It undoubtedly set us back as a world community. The pandemic generation of learners will never forget the scars of this terrible time.

“But the pandemic wasn’t felt in the same way by all children. It was those most vulnerable children and young people in humanitarian settings – battling conflict, climate emergencies, the hunger crisis, poverty, or all of this combined – who have felt the pain most keenly.”

Education Cannot Wait (ECW) - the global fund for education in emergencies and protracted crises - and its strategic partners, including Save the Children, are calling on bilateral donors and foundations to provide at least $1.5 billion to ECW ahead of a high-level financing conference next February to a 2023-2026 plan.

ECW works through the UN multilateral system to both increase the speed of responses in crises and connect immediate relief and longer-term interventions through multi-year programming.

In September 2021, Save the Children published the Build Forward Better report,[iii] choosing this title to highlight the need not to just build ‘back’ to how things were but to build forward better and differently.

That report included the first Risks to Education Index which ranked countries by the vulnerability of their school system to hazards, vulnerability and deficiencies in preparedness. This enabled us to make a holistic view of the risks to education and suggest which national education systems required greater resources from national governments and international actors to mitigate crises.

ENDS

MEDIA CONTACT: Jess Brennan on 0421 334 918 or media.team@savethechildren.org.au.

Notes to Editor:

[i] You can find Save the Children’s Build Forward Better report 2022 here.

[ii] According to World Bank population data for 2022, Afghanistan, Mali, Somalia and Sudan have a combined total of about 49 million school aged children aged 5 to 19.

[iii] In Sudan, nearly 7 million children, or one in three school-age children, do not attend school in Sudan, according to new data from international groups working in Sudan.

The Risks to Education Index 2022 uses the below indicators to rank countries by the vulnerability of their school system to hazards, and deficiencies in preparedness:

- Vulnerability to climate change in combination with its readiness to improve preparedness.

- Children’s access to education in humanitarian crises – including the scope and scale of attacks on education and the number of internally displaced children.

- Percentage of youth unemployment.

- Factors related to learning outcomes and percentage of school-aged children with an internet connection at home.

- Percentage of out-of-school primary school aged children.

- COVID vaccination coverage among the population, and whether teachers are prioritised for the vaccine.